Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Biochemical Technology

Investigation Obtaining of Radionuclide Sulfur-35 without а Carrier from Chlorine Containing Compounds in a Reactor WWR-SM

Department of Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Technologies of the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Academy of Sciences, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan

Author and article information

Cite this as

Ashrapov U, et al. Investigation Obtaining of Radionuclide Sulfur-35 without а Carrier from Chlorine Containing Compounds in a Reactor WWR-SM. J Clin Microbiol Biochem Technol. 2026; 12(1): 001-010. Available from: 10.17352/jcmbt.000060

Copyright License

© 2026 Ashrapov U, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.The article presents methods for obtaining sulfur-35 radionuclide without a carrier from neutron-irradiated potassium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, and carbon tetrachloride. The methods of irradiation of targets from chlorine-containing compounds with thermal neutrons in the vertical channel of the WWR-SM reactor, methods of processing irradiated targets, and the extraction of sulfur-35 without a carrier are presented. The highest yield of sulfur-35 activity per 1 g of chlorine-containing compound (3.312 Ci/g) is achieved by irradiating CCl4 targets under the following conditions: thermal neutron flux density is 1·1014 n/cm2sec, irradiation time is 2000 hours, nominal reactor power is 10 MW, and irradiation of a quartz ampoule with the target in a vertical reactor channel with mandatory cooling of the target with running first loop water. The isolation of sulfur-35 without a carrier from irradiated carbon tetrachloride was carried out using the water extraction method, which is the simplest and does not require complex radiotechnological operations.

The radionuclide sulfur-35 has a half-life of 86.35 +/- 0.17 days [1] and emits only beta particles with a maximum energy of 0.167 MeV and an average energy of 0.049 MeV, so 35S does not pose an external hazard to humans, since beta particles from 35S practically do not penetrate the dead layer of skin on the hands. However, the main danger of the sulfur-35 radionuclide is its entry into the body through the upper respiratory tract through the mouth and intraureteral irradiation [2]. For most 35S-labeled compounds, the entire body is the critical organ. Urine testing is an effective sampling method for determining whether 35S has been absorbed into the body. Cosmic radiation reaching Earth’s upper atmosphere is predominantly made of high-energy, positively charged particles, mainly protons (~87%) with energies from≈ 10

Cosmogenic isotope 35S is widely used to understand chemical and physical processes in the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and cryosphere [7]. It`s used as an indicator of atmospheric processes because it is continuously formed in the stratosphere, from where it is transported to the troposphere or lower atmosphere, and finally it enters groundwater with rain. Cosmogenic sulfur-35 is a residence time indicator suitable for determining the age of groundwater in the range of three to nine months [8]. Cosmogenic 35S in the form of sulfate aerosols (35SO42-) has been used as a tracer of air masses originating from the stratosphere and transported downwards, to quantitatively measure the rotation processes of stratospheric air masses [9]. A series of experiments was conducted to determine the deposition rate, distribution, and subsequent loss of 35S in crops [10]. A rapid and reliable method for the analysis of extremely low concentrations of 35S in rainwater and lake water samples is presented, opening the door to a variety of future applications of this 35S tracer for studying environmental sulfur cycling and for age determination of lake water and shallow groundwater [11]. The paper [12] presents a new analytical method for the analysis of large quantities of BaSO4 for 35S, providing counting efficiencies comparable to published liquid scintillation spectroscopy methods despite a tenfold increase in the amount of SO4 sample. The study [13] describes a rapid and reliable method for analyzing extremely low levels of 35S in rainwater and lake water samples.

The production of S-35 radionuclide is carried out in a nuclear reactor by irradiating KCl or NaCl according to the reaction 35Cl(n,p)35S [14] and, to a lesser extent, by the poisonous reaction 34S(n,γ)35S [15]. Also this reactions are triggered by neutron activation of impurities in reactor coolants or solid materials [16]. Radionuclide S-35 is released into the environment in small quantities during normal operation of gas-cooled reactors due to leakage of reactor coolant into the atmosphere [17]. The work [18] showed that during radiolysis of ion-exchange resins used in reactor cleaning systems, sulfur-35 and phosphorus-32 were detected, which are formed as a result of the decay of radioactive sulfur-35 into phosphorus-32. Sulfur-35 tressers are widely used where sulfur analysis is required (feed additives, synthetic resins, fertilizers and fertilizer additives, animal medicines, pigments, petroleum products, detergents, sheet metal, explosives, some batteries, paper, insecticides, tires, gunpowder, fireworks, matches, rubber, cosmetics, shampoos, fabrics, adhesives, and others.

The artificial radionuclide 35S (along with the radionuclide 32P) was first used as a radioactive label in the Hershey-Chase experiments [19]. It is well known that proteins contain oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and sulfur, whereas nucleic acids contain oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus. Sulfur is present in proteins but absent in DNA, while phosphorus, on the contrary, is present in DNA but absent in proteins. Hershey and Chase, using radioactive labels sulfur-35 and phosphorus-32, experimentally demonstrated that phages inject their DNA, not protein, into bacterial cells. The Hershey-Chase experiment demonstrated that the carrier of genetic information in cells is not proteins, as previously thought, but DNA.

The study [20] using a radioactive label with the radionuclide 35S showed that sulfur-oxidizing bacteria are capable of metabolizing sulfur-containing compounds (thiosulfate) into less harmful products, such as elemental sulfur (S).

Study [21] showed that the intake of the sulfur-35 radioisotope into the human body can be assessed by measuring its amount in biological tissues or products (urine, blood, feces, hair, or sweat). The biological analysis method includes monitoring urine for the presence of the sulfur-35 radioisotope. Study [22] showed that two types of deciduous trees (yellow poplar, acacia, and red maple) in the Walker Branch watershed near Oak Ridge, Tennessee, were radiolabeled with sulfur-35 to study the internal cycling, accumulation, and biogenic release of sulfur (S). The article [23] reports on the synthesis of three key compounds of the human gasotransmitter (cysteine trisulfide, glutathione trisulfide, and GYY-4137), which were isolated from hydrogen sulfide labeled with the radioactive isotope 35S. The study [24] discusses the limitations of nuclear 35S rDNA markers (such as the number of loci, transcriptional activity, nucleolar dominance) based on cytological and karyological experimental work in order to make informed biological and evolutionary conclusions in plant evolution. Radionuclide 35S can also be used in tRNA research, where it serves as a precursor for the formation of selenium-containing compounds such as 5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenuridine [25].

The radiotracer Na235SO4 enriched with S-35 is the only commercially available product, and the cost of the sulfur-35 radionuclide without carrier, having an activity of 1 mCi (37 MBq) and a specific activity of 1050-1600 Ci (38.8-59.2 TBq)/mmol sodium sulfate in 1 ml of water, is US$1354.00–1604.49. In this regard, obtaining the 35S radionuclide without a carrier, possessing high specific activity and radiochemical purity, by irradiating unenriched, cheap natural chlorine-containing compounds with neutrons from a reactor, is an urgent task.

An important condition for obtaining the 35S radionuclide with high specific activity in the WWR-SM reactor is the high thermal neutron flux density, which is achieved by using a fuel assembly with highly enriched uranium (IRT-3M with 36% enrichment of U-235) as nuclear fuel. However, in 2018, at the request of the IAEA, based on the The Reduced Enrichment for Research and Test Reactors (RERTR) Program [26,27], the WWR-SM reactor was converted to low-enriched fuel of the IRT-4M type with an enrichment of U-235 of 19.7% and for this purpose, NIKIET (Joint Stock Company “N.A. Dollezhal Scientific Design Institute of Power Engineering, Order of Lenin”, Russia) developed a low-enriched fuel assembly of the IRT-4M type, intended for use in the WWR-SM research reactor [28].

Research objectives: to find the most suitable chlorine-containing target, to optimize the target loading mode in the vertical reactor channel, and to develop a technology for producing highly active sulfur-35 without a carrier.

This study aims to irradiate targets made of chlorine-containing chemical compounds with neutrons in a reactor, to select the optimal mode for irradiating carbon tetrachloride targets with neutrons in a reactor, and to obtain high specific activity of sulfur-35 radionuclide with radiochemical purity.

Materials and methods

Technical characteristics of the WWR-SM reactor

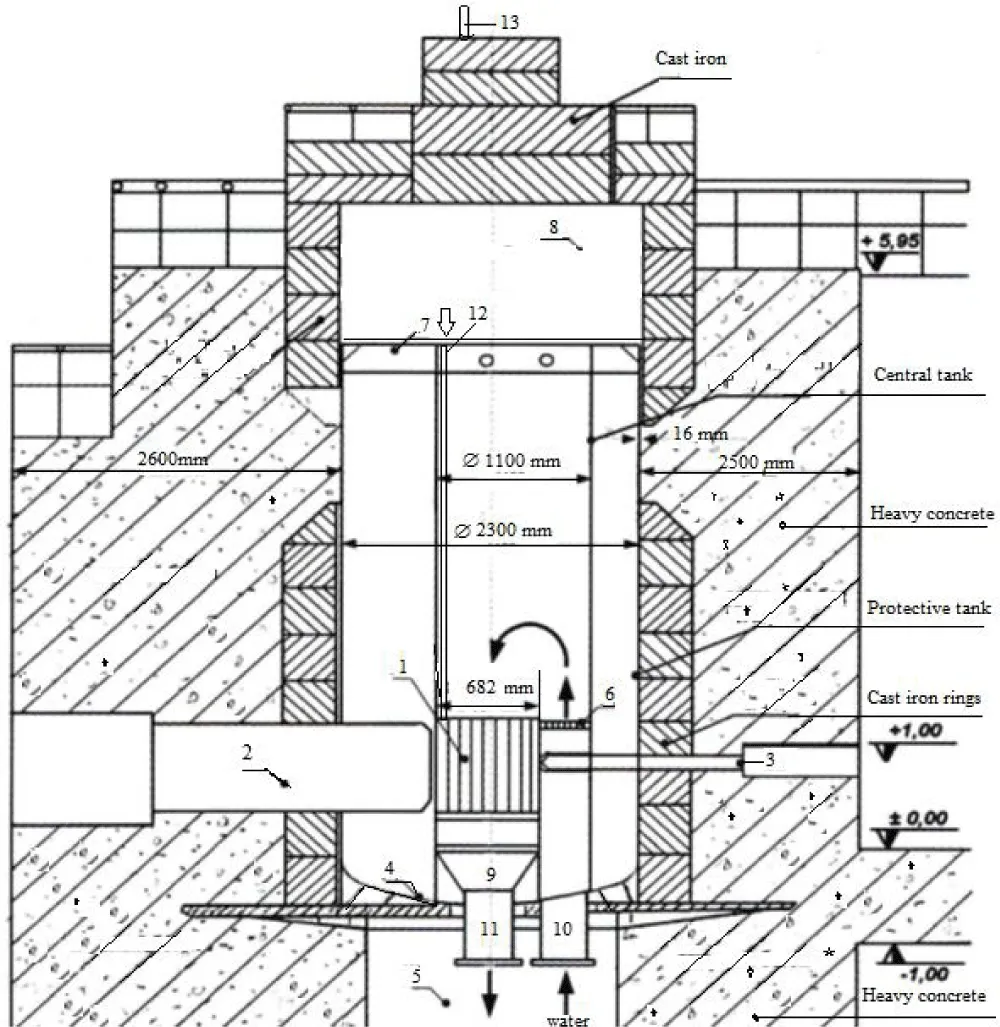

The WWR-SM (pressurized water reactor of serial modernization) reactor is one of the safest research reactors in the former Soviet Union. The WWR-SM reactor is a heterogeneous reactor in which ordinary distilled water serves as a neutron moderator, coolant, and biological shield [29]. The reconstruction of the WWR-SM reactor in 1978 led to an increase in its capacity from 2 to 10 MW, and in 2002, the WWR-SM reactor switched to using highly enriched uranium-235 (36%) fuel. IRT-3M allowed for a significant expansion of materials science research on it [30]. Table 1 shows the technical characteristics of the WWR-SM reactor.

Figure 1 shows a structural diagram of the WWR-SM reactor.

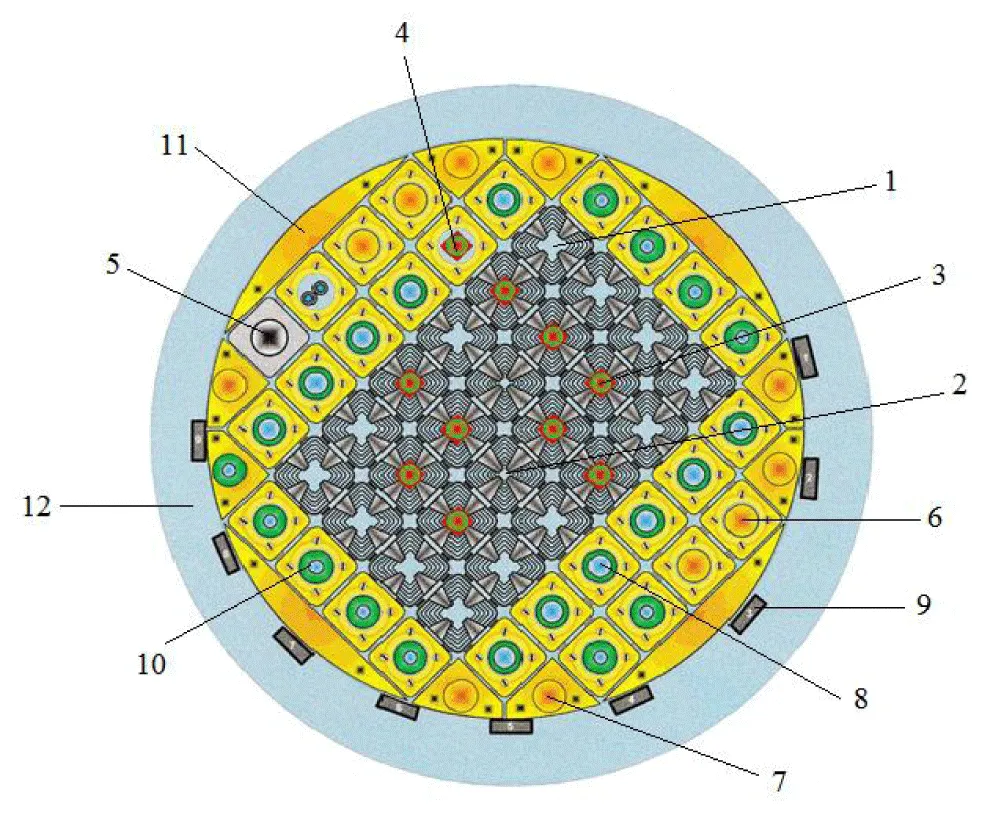

Figure 2 shows a cartogram of the active core of the WWR-SM reactor (example).

Results and discussion

Irradiation process of chlorine-containing targets

The radionuclide 35S is obtained in a nuclear reactor during irradiation of organic and inorganic chlorine-containing compounds by thermal neutrons of a nuclear reactor. There is no reliable information in the literature on the activation cross-section and threshold energy of neutrons. The activation cross section of the above nuclear reaction ranges from 0.35 [31] barn to 0.575 [32] barn. In experiments, we used the activation cross-section average value 0,6375 barn.

The decay of the S-35 atom is accompanied by the formation of a Cl-35 atom, an electron, and an antineutrino in the nuclear reaction:

The process of irradiating chlorine-containing targets consists of the following stages:

Stage 1: Preparation of the target for irradiation. In the experiments, the neutron activation of the following chlorine-containing compounds was investigated: KCl - potassium chloride 99,9% (special purity); NaCl - sodium chloride 99,9% (chemically pure); MgCl2·6H2O - magnesium chloride 6-hydrate (clean for analysis); СС14 - carbon tetrachloride (clean for analysis). All chlorine-containing compounds met the requirements of the state standard. Potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), each weighing 1.0 g, were placed in quartz ampoules with an inner diameter of Ø = 4 mm and a length of l = 50 mm, and then ware sealed at a temperature of 1600–1700 °C.

Stage 2: Preparation of targets of Co-60 monitors. Several batches of Co-59 tracking monitors were manufactured: Co-59 monitors (cobalt alloy with 0.1% Co-59) in the form of metal discs (Ø = 3 mm, h = 0.2 mm, m = 3.0 mg), each of which was individually wrapped in aluminum foil, and then each monitor together with targets of potassium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, and carbon tetrachloride (each weighing 1.0 g) was placed in quartz ampoules and sealed.

Stage 3: Loading the aluminum block container with the target into the reactor’s active core and process irradiation them by neutrons. Sealed quartz ampoule with chlorine-containing target, standard. Potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), each weighing 1.0 g, were placed in quartz ampoules with an inner diameter of Ø = 4 mm and a length of l = 50 mm, and then ware sealed at a temperature of 1600–1700 °C.

Stage 2: Preparation of targets of Co-60 monitors. Several batches of Co-59 tracking monitors were manufactured: Co-59 monitors (cobalt alloy with 0.1% Co-59) in the form of metal discs (Ø = 3 mm, h = 0.2 mm, m = 3.0 mg), each of which was individually wrapped in aluminum foil, and then each monitor together with targets of potassium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, and carbon tetrachloride (each weighing 1.0 g) was placed in quartz ampoules and sealed.

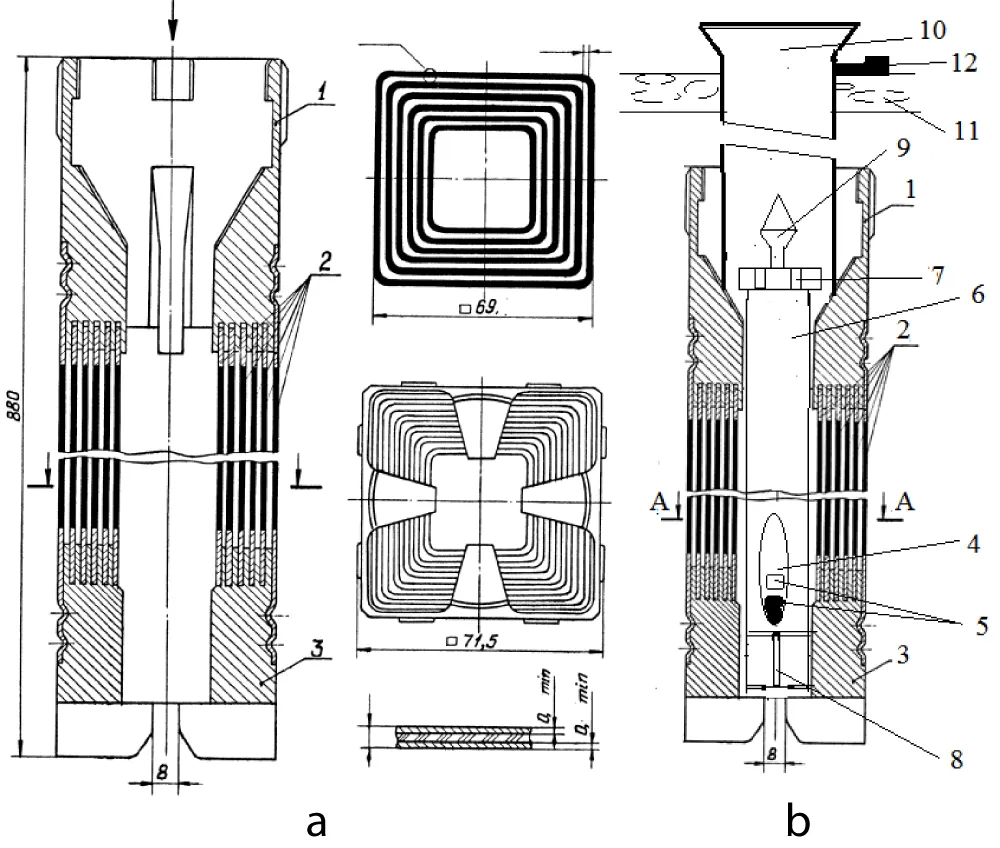

Stage 3: Loading the aluminum block container with the target into the reactor’s active core and process irradiation them by neutrons. Sealed quartz ampoule with chlorine-containing target, along with a cobalt monitor, was placed in a special aluminum block container (dimensions: length – L = 750 mm, diameter – Ø = 20 mm). Next, the block container was placed into the inner hollow space of the IRT-4M fuel assemblies in the reactor’s active core using an aluminum lifting boom 6 m long. Irradiation of the chlorine-containing target along with the Co-59 monitor was made under the following conditions: thermal neutron flux density ≥1·1014 n/cm2·s, irradiation time 2000 hours, nominal reactor power 10 MW.

Stage 4: Unloading the irradiated target from the reactor core after irradiation. After the target has been irradiated, it is unloaded from the reactor’s active core to ‘hot cells,’ and then the lid of the block container is opened. The irradiated target and monitors were removed from the quartz ampoules by cutting the quartz ampoules.

Stage 5: Measurement of sulfur-35 activity. After the radiochemical processing of the target (dissolution in water) and obtaining an aliquot, the aliquots were measured on a gamma-beta spectrometer of “Progress BG (II)” BDEB 3-2U with the software “Progress 5”. Co-59 monitors on the gamma-beta spectrometer were measured. The confidence limits of the total error of the measurement result of external beta radiation at a probability of 0.95 were within ± 20%.

The formula for the definition of the activity of radionuclide S-35 is:

where: Q - activity of S-35, mCi; Ft - thermal neutrons flux density, neutrons/cm2sec;

t0 - irradiation time of sample, sec; T1/2 - half-life S-35, sec; q - enrichment of S-35, %;

m - weight of target S-35, g; st - activation cross section of reaction 35Cl (n, p) 35S, barn.

Stage 6: Measurement of Co-60 activity and determination of thermal neutron flux density. Thermal neutron flux density determination by the following formula was made:

where: Fn − thermal neutrons flux density, neutrons/cm2·sec; A − measured activity of the monitor, imp/sec; N – number of kernels Со-59 (4.4⋅1016 kernels/cm2); t1 − irradiation time, sec; σ − cross section of radionuclide 60Co, barn; t0 − irradiation time of monitor,sec; σ − activation cross section of reaction 59Co (n, γ) 60Co, barn; λ − decay constant (60Cо); T½ − half-life (60Со), sec; eλt = 0.693·t / T1/2

The total effective activation cross-section (δeff) is formed by multiplying the thermal neutron activation cross-section by the coefficient of KCd. Therefore, the formula for calculating the induced activity of the radionuclide 35S takes the following form:

where: Q - activity of S-35, mCi; Ft - thermal neutrons flux density, neutrons/cm2sec;

t0 - irradiation time of sample, sec; T1/2 - half-life S-35, sec; θ - enrichment of Cl-35, %;

θ1- mass fraction of chlorine in a chlorine-containing compound; m - weight of target weight of chlorine-containing compound, g; δt - activation cross section of reaction 35Cl(n, p)35S, barn.

The final, most complete formula for determining the thermal neutron flux density is as follows:

where: Fn − thermal neutrons flux density, neutrons/cm2·sec; S - area of the detector photopeak without Cd screen, imp/sec; Scd − area of detector photo peak in Cd screen, imp/sec; A - atomic weight of Co-59; λ - decay constant of the isotope Co-60, sec-1; σ - Co-60 activation cross section, barn (0,6375 x 1·10-24 cm2); Rγ - gamma ray output; θ - isotope content in the detector; ε- analyzer sensor efficiency (3,53·10-3); P- reactor power, MW; m – detector mass, g (m = 3·10-5g); mCd - mass of the detector in the Cd screen, g; t0–irradiation time of detector without Cd screen, sec; t0 Cd - irradiation time of detector with Cd screen, sec; texp – exposure time of detector without Cd screen, sec; texpCd - exposure time of detector with Cd screen, sec; τm– measuring time of detector without Cd screen, sec; τm Cd - measurement time of detector with Cd-screen, sec.

Determination of the cadmium ratio value for isotope 35S

When calculating the induced activity of sulfur-35 using the formula (4), there is no contribution of fast neutrons to the activation above the initial ingredient. In order to pay attention to the thermal neutrons on the activation of the irradiated target, we studied the cadmium ratio (RCd). The measurement of the cadmium ratio RCd is found from the results of two measurements. First of all, a target without a cadmium sheath is placed in the neutron field. It is activated by both thermal and resonant neutrons. After determining the induced activity A1 and holding for a period during which almost all active nuclei will decay, the target is wrapped in a cadmium sheath (screen) and placed back in the same place in the neutron field.

Cadmium has unusually high thermal neutron capture cross sections (7200 barns), and hence the radioactivity induced in cadmium-wrapped targets is approximately proportional to the intermediate neutron flux. The cadmium ratio RCd is equal to the ratio of the effect of activation by thermal neutrons to the effect of activation by resonant neutrons: To determine the cadmium ratio, 10 weighed portions of potassium chloride samples were irradiated with and without a cadmium screen under the same conditions: thermal neutron flux Fn = 1·1014 neutrons/cm2sec, and irradiation time is 1.0 hour. Knowing RCd, it is easy to take into account the contribution of neutrons when irradiating a sample above the cadmium region of the neutron spectrum using the formula:

where: RCd - cadmium ratio; KCd - target activation coefficient in excess of the cadmium region of the neutron spectrum (En1.0 eV). Table 2 shows a cadmium ratio value for radionuclide 35S.

As can be seen from Table 2, the cadmium ratio for radionuclide 35S is 9.37, which indicates that the nuclear reaction 35Cl(n,p)35S proceeds exclusively by thermal neutrons with energy En = 0.0253 eV [33].

Irradiation of carbon tetrachloride target in active core of reactor WWR-SM

The carbon tetrachloride target was placed in a sealed quartz ampoule, which was placed in a special aluminum block container with dimensions of length l = 750 mm and diameter ∅ = 20 mm. This block container has two openings in its body: one opening on the bottom and two openings on the lid. These openings are designed to cool the target with running water from the reactor’s primary circuit. The water of the first circuit enters through the upper inlet openings into the block-container, cools the irradiated target (carbon tetrachloride), and then exits through the lower outlet opening. The aluminum block container was loaded into the hollow central space of a 6-tube fuel assembly of the IRT-4M type in the active WWR-SM reactor using a 6-meter rod with a gripper. The targets were irradiated under various time conditions from 100 to 2000 hours at a nominal reactor power of 10 MW and a thermal neutron flux density of 1 1014 n/cm2 s.

Figure 3 shows a 6-tube fuel assembly IRT-4M (a) and a special aluminum block container with irradiation target and design for fastening the irradiation channel to the reactor platform (b).

Determination of thermal neutron flux density by using Co-59 monitors

Usually, in low-power reactors (including reactor WWR-SM) for measurement of thermal neutron flux densities, monitors Co-59, Na-24, Mo-98, Dy-164, In-113, In-115, Mn-55, Cu-63, Cu-65, Au-197, or monocrystalline silicon [34,35] can be used. But, for determining the thermal neutron flux density, the most convenient tracking monitors are the Co-59 and Au-197.

Table 3 shows the main nuclear-physical characteristics of neutron activation detectors of thermal and resonance neutrons.

Table 4 shows nuclear-physical characteristics of the tracking monitor (detector) Co-59. In our experiments, to determine the thermal neutron flux density, we used Co-59 monitors, which are stable at high temperatures and have the most convenient nuclear-physical characteristics.

Optimization of the target irradiation process

In the vertical channels of the WWR-SM reactor for local monitoring of the thermal neutron flux density, a small-sized thermal neutron sensor (TND-2.0) was used. TND-2.0 is operating depending on 5 × 1012 neutron/cm2sec to 5 × 1014 neutron/cm2sec in gaseous media and in water [36-39]. The TND-2.0 is made of two main functional parts: a sensitive element made of a material (alloy) containing a fissile material (uranium), and a non-volatile energy converter with an electrical output signal, which is a differential thermocouple. Under the influence of neutron irradiation, the energy of nuclear fission reactions is converted into thermal energy in the sensitive element, then part of the thermal energy is converted into electrical energy using a differential thermocouple in thermal contact with the sensitive element. The sensitive part of the TND-2.0 (uranium-nickel alloy) is connected to the current device by an insulated thermocouple cable.

Method for measuring the thermal neutron flux density is following: Thermoneutron sensor TND-2.0 (primary device) was rigidly fixed at the end of a 6 m long aluminum rod, the rod was loaded into a vertical irradiation channel and, at a reactor power of 300 kW was irradiated, than arising in TND-2.0 the potential difference was measured using a Z-4833 potentiometer (secondary device). Measurement of the potential difference at each point was carried out during 15÷20 second, and the distance between each fixed measurement point was 5 cm, starting from the top of the vertical channel and ending at the bottom of the irradiation channel. Next, at the measured point with the maximum value of the potential difference, Co-59 track monitors in the form of metal disks

(∅ = 3 mm, h = 0.2 mm, m = 3.0 mg) made of an alloy of aluminum and cobalt (0.1%) without cadmium screens and with cadmium screens of two types (KE-1 with a thickness of 0.5 mm and KE-2 with a thickness of 1.0 mm) were attached to the end of the aluminum rod. Table 5 shows the potential differences in the vertical channels of the WWR-SM reactor measured by the TND method.

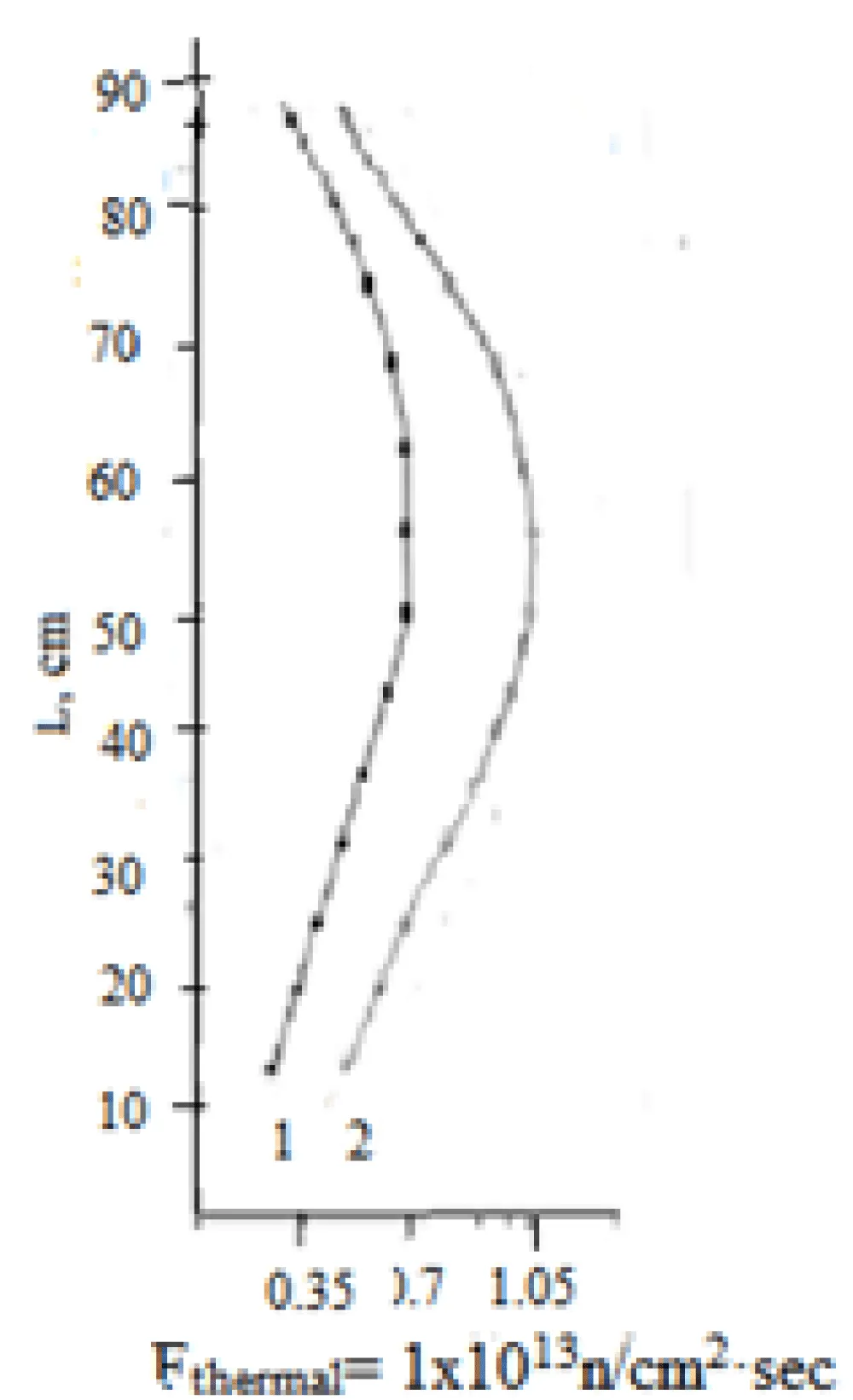

Table 5 shows that the potential difference is greatest at a distance of 35-45 cm from the top of the vertical irradiation channel (the middle section of the fuel assembly). Accordingly, the thermal neutron flux density is also greatest in this section of the vertical channel.

Co-59 monitors, also at a reactor power of 300 kW for 15-20 seconds, were irradiated at the location where the maximum potential difference occurs (40 cm from the top of the channel). Activity of the formed radionuclide Co-60 (in the monitors Со-59) was measured by SU-01P multichannel pulse analyzer with a DGDK-100 Ge-Li detector with Aspekt, Angamma program and also by DSA1000 Canberra HP multichannel gamma spectrometer with Ge detector with the standard Genie 2000 software package between each fixed measurement point was been 5 cm starting from the top of the vertical channel and ending at the bottom of the irradiation channel. The efficiency of the detector of the gamma-spectrometer is defined by means of the standard Со-60 from a complete set of etalon spectrometric gamma sources (Reference-standard Closed Radionuclide Sources).

In the next step, in the vertical channels of the reactor, in the gap with the maximum potential differences (35-45 cm from the top of the fuel element), Co-59 monitors were irradiated during 48-50 hours at reactor power 10 MV and their activity was measured, and then the thermal neutron flux densities were determined using formula (5). Table 6 shows thermal neutron flux density (maximum values) in the reactor vertical channels determined by 59Co monitors.

As shown in Table 6 highest thermal neutron flux density (6.9·1013 n/cm2·s) is observed in the vertical channel №5-5.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the thermal neutron flux density in the vertical irradiation channel of the WWR-SM reactor, determined by the TND method.

From Figure 4, it can be seen that the thermal neutron flux density has its highest values at a distance of 35-45 cm from the top point of the vertical irradiation channel, which corresponds to the middle of the 6-tube fuel assembly IRT-4M.

Thus, to optimize the process of neutron irradiation of chlorine-containing targets, it is recommended to place them for irradiation with thermal neutrons in the central part of the irradiation channel, at a distance of 35-45 cm down from the top of the channel or 35-45 cm from the top of the head of the IRT-4M fuel assembly.

Induced activity of S-35 and the practical output activity of S-35

The induced activity and practical yield of the radionuclide C-35 depend on the target irradiation time and the thermal neutron flux density. Table 7 shows the value of the induced activity and the practical output activity of S-35 depending on the irradiation time (thermal neutron flux density 1· 1014 n/cm2·sec).

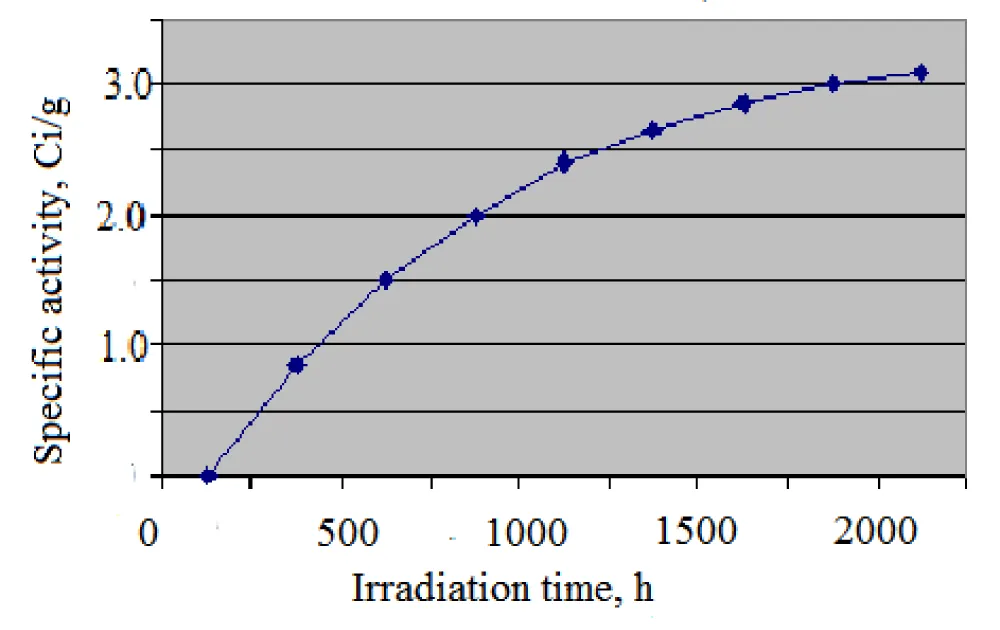

As can be seen from Table 8, the highest specific activity of the sulfur-35 radionuclide occurs when carbon tetrachloride targets are irradiated for 2000 hours. The obtained experimental results show that the maximum specific activity of the S-35 radionuclide (3.422 Ci/g) was obtained by irradiating carbon tetrachloride targets with thermal neutrons, which is 2 times greater than by irradiating with thermal neutrons of potassium chloride targets. This proves that the chlorine-containing compound carbon tetrachloride is the most suitable target for obtaining high activity carrier-free sulfur-35.

Figure 5 shows the accumulation curve of sulfur-35 at thermal neutrons flax density of 0.8·1014 n/cm2sec.

Thus, by irradiating the target in the center of the active zone, or closer to the beryllium reflector, or inside the fuel assembly in a special container in the middle of the vertical channel, and with an irradiation time of up to 2000 hours at a reactor power of 10 MV, it is possible to achieve a high specific activity of the target sulfur-35 radionuclide.

Purification of S-35 from impurity radionuclide P-32

At the WWR-SM reactor, the value of integral fast neutrons with energy Fn >10 MeV in the overall neutron spectrum is 5–6 orders of magnitude lower than that of thermal neutrons. Therefore, during the irradiation of chlorine-containing targets at reactor, fast neutrons make the smallest contribution to the formation of radionuclides. In addition, when targets are irradiated with fast neutrons, several radionuclides with very short half-lives are formed, which decay within 20÷25 hours after irradiation (34Cl, 38Cl, 34P, 42K ) (Table 8).

As shown in Table 8, the most significant radionuclide that can be a radionuclide impurity for S-35 is the radionuclide 32P with a half-life of 14.5 days, which is formed as a result of the nuclear reaction 35Cl(n, α)32P.

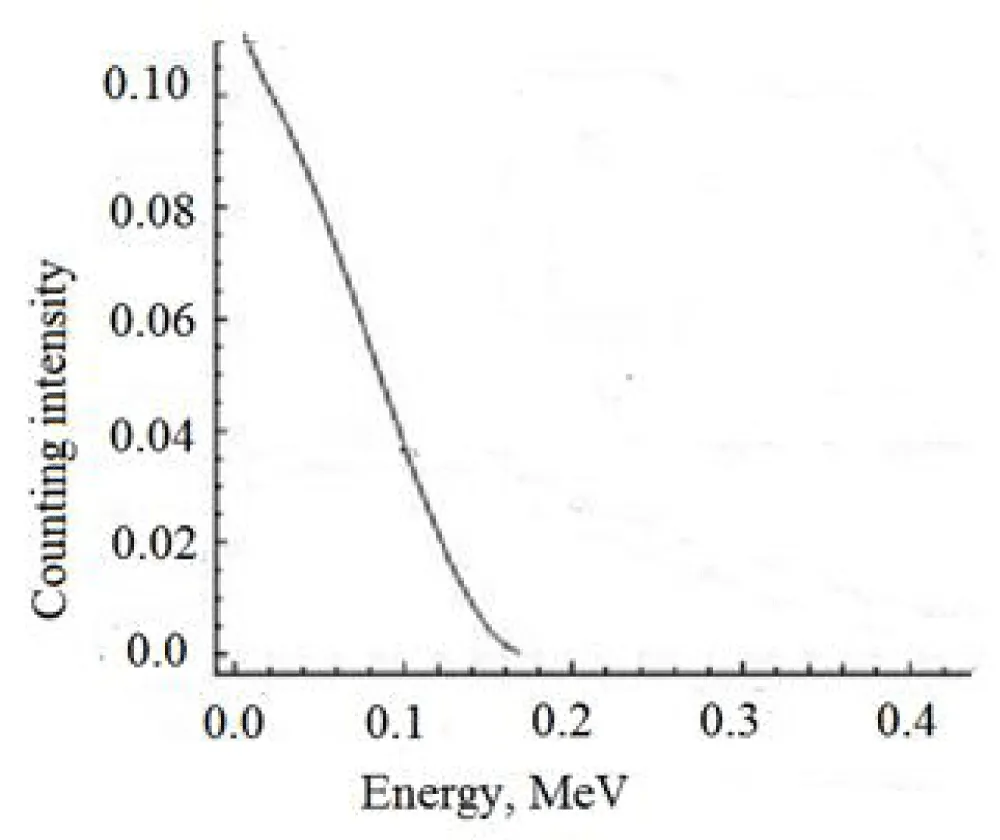

If you look at the energy spectrum of beta radiation of the radionuclide 35S, you can see that it has a maximum energy of Eβ = 0.167 MeV (Figure 6).

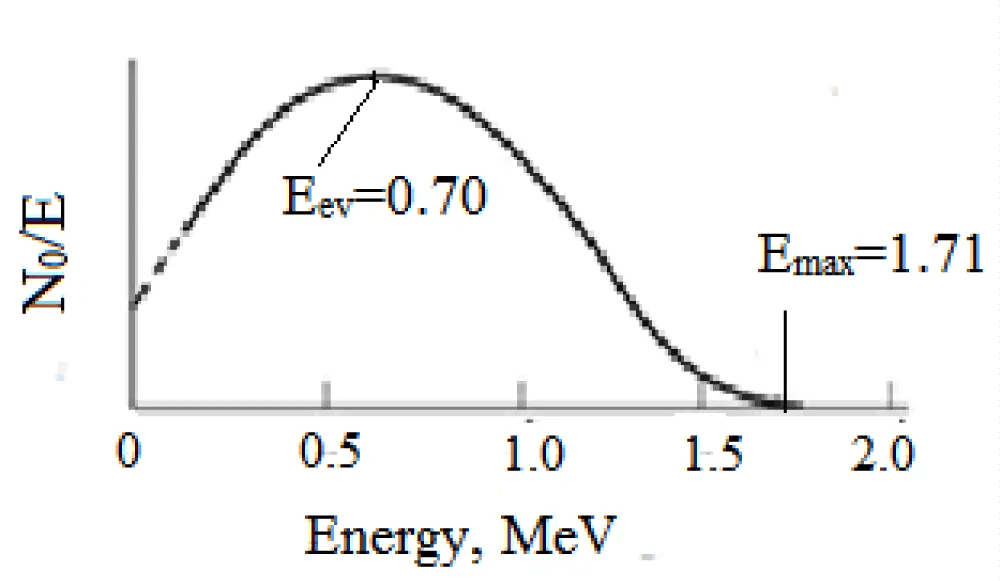

From the energy spectrum of beta radiation of the radionuclide 35S (Figure 6), it is clear that it has a maximum energy of Eβ = 0.167 MeV, which is more than 10 times less than the energy spectrum of the radionuclide P-32 with a maximum energy of 1.71 MeV (Figure 7).

By comparing these two spectra (Figures 6,7), it can be concluded that the presence of phosphorus-32 in the target radionuclide greatly distorts the result of measuring the activity of the sulfur-35 radionuclide, so it is important to purify the target sulfur-35 radionuclide from the admixture of phosphorus-32 radionuclide.

To separate the target sulfur-35 radionuclide from radionuclide impurities, various radiochemical methods are used, such as precipitation, ion exchange, extraction, and sublimation.

A study of the literature showed that the review presents methods for the isolation of 35S sulfur without a carrier from alkaline chloride matrices [40]. Study [41] presents a method for the separation of S-35 from a KCl target exposed to neutrons in a reactor, and the separation of S-35 from P-32 was carried out on a strongly basic anion exchanger Dowex-1. In, a carrier-free method was developed for the separation of radionuclides 32P and 35S from a neutron-activated potassium chloride target.

The irradiated potassium chloride target was dissolved in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid solution and then adsorbed on a chromatographic column with aluminum oxide (m = 5.0 g). Then the chromatographic column was washed with distilled water to remove K+ and Cl– ions. The 35S radionuclide was eluted with 1.0 N ammonia solution. The eluate contained (NH4)235SO4. It is known that for the extraction of radionuclide 35S in the form of sulfate, a method is used based on the absorption of [35SO4]-2 - ions on chromatographic aluminum oxide. A solution of irradiated NaCl in 0.5 N HCl is passed through a tube with Al2O3, on which both the target radionuclide 35S and the impurity of radionuclide P-32 are sorbed. Then the column is washed with water, and then sulfur-35 is washed out with a 1.0 N ammonia solution. The radionuclide 32P impurity remained sorbed on the sorbent. The sulfur yield is about 90%, and the radiochemical purity of radionuclide 35S reaches 99.9% [31]. The irradiated targets of sodium chloride and magnesium chloride were processed similarly.

The method for purifying the target product from radionuclide impurities is as follows: carbon tetrachloride is chemically inert, does not react with air, and is stable to light, but its boiling at 76.7 °C, because irradiated CCl4 target was opened after cooling in dry ice—a solid form of carbon dioxide kept at a temperature below –78.5 °C to prevent the CCl4 from evaporating. Next, the ampoule containing the liquid irradiated CCl4 was transferred to a separatory funnel, an aqueous solution of 1.0 N ammonia was added, and the separatory funnel and its contents were vigorously shaken. Since carbon tetrachloride is immiscible with the aqueous phase, the 35S radionuclide, in the form of (NH4)235SO4, quantitatively transfers into the aqueous phase upon shaking the contents of the separatory funnel. The water contains the target radionuclide 35S, while the radionuclide impurity 32P remains in the CCl4. Thus, the extraction process was performed manually in a protective hood: irradiated liquid CCl4 was placed in a glass separatory funnel, then an aqueous solution of 1.0 N ammonium hydroxide was added, and the funnel and its contents were shaken several times. This ensured quantitative transfer of the 35S radionuclide into the aqueous phase.

During radiochemical processing of the target by the extraction method, the coefficient of extraction of the radionuclide 35S from the organic phase into the aqueous phase has a high value:

The recovery factor of S-35 from the organic phase to the aqueous phase is 12.5, and the target carrier-free S-35 radionuclide has a yield of > 92%.

Conclusion

When comparing the activity of different irradiated targets, the specific activity of the S-35 radionuclide obtained from a carbon tetrachloride target is approximately 2 times higher than the specific activity of S-35 obtained from a sodium chloride target. This is due to the fact that the mass fraction of sulfur in CCl4 has the highest value - 92.5%, while the proportion of sulfur in NaCl is 60%, in MgCl2 - 74%, and in KCl - 45%.

When irradiating a target made of KCl, NaCl, or MgCl2 with thermal neutrons, it is necessary to first dissolve the target and then adsorb it into a chromatographic column to isolate radionuclide S-35 and purify it from radionuclide impurities, the use of which reduces the yield of the target product S-35 to 60% - 70%. In the case of irradiation of a carbon tetrachloride target with thermal neutrons, the method of separating the activated target product (S-35) from the irradiated target (CCl4) is the simplest (extraction) and does not require complex radioactive operations. However, carbon tetrachloride target samples must be irradiated in vertical reactor channels with mandatory cooling by water of the reactor’s primary circuit, since at high temperatures carbon tetrachloride passes from the liquid phase to the gaseous phase (boiling point = 76.6 °C), which we observed during the irradiation of targets in the “dry” channel (No. 9 and No. 3) of the reactor (the ampoule with carbon tetrachloride became depressurized).

The highest yield of radionuclide 35S activity per 1.0 g of chlorine-containing compound, ~3.312 Ci/g, is achieved by irradiating CCl4 targets under the following conditions: thermal neutron flux density ≥0.8·1014 n/cm2sec, irradiation time 2000 h, nominal reactor power 10 MW, and irradiation of a quartz ampoule with the target in a vertical reactor channel with mandatory cooling of the target. The separation of radionuclide 35S without a carrier from irradiated CCl4 and from the possible radionuclide 32P is carried out by a simple method of extraction with water.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have led to the results of the work presented in this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out using basic funding allocated to the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

- Cooper RD, Cotton ES. Half-life of sulfur-35. Science. 1959;129(3359):1360–1361. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.129.3359.1360

- Zoon RA. Safety with 32P- and 35S-labeled compounds. In: Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 152. New York: Academic Press; 1987;25–29. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(87)52006-7

- Mironova IA, Aplin KL, Arnold F, Bazilevskaya GA, Harrison RG, Alexei AA, et al. Energetic particle influence on the Earth’s atmosphere. Space Sci Rev. 2015;194. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11214-015-0185-4

- Monem AA. Cosmogenic radionuclides in the atmosphere: origin and applications. 2013;35–45. Available from: https://inis.iaea.org/records/63gkz-9j375

- Fastovsky VG, Rovinsky AE, Petrovsky YuV. Discovery. Origin. Prevalence. Application. Inert gases. Moscow: Atomizdat; 1972;3–13.

- Lin M, Zhang Z, Su L, Su B, Liu L, Tao G, et al. Unexpectedly high 35S concentration indicates strong downward transport of stratospheric air during the monsoon-to-monsoon transition period in East Asia. Geophys Res Lett. 2016;43(5). Available from: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016GeoRL..43.2315L/abstract

- Collins C, Cunningham N. Modelling the fate of sulphur-35 in crops. 1. Calibration data. Environ Pollut. 2005;133(3):431–437. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2004.07.001

- Lin M, Wang K, Kang S, Thiemens MH. Simple method for high-sensitivity determination of cosmogenic 35S in snow and water samples collected from remote regions. Anal Chem. 2017;89(7):4116–4123. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.6b05066

- Dierssen D, Niemann PO. Radioactivity of seawater induced by slow neutrons. Acta Radiol. 1955;43:421–427. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/00016925509172507

- Uriostegui SH, Bibby RK, Esser B, Clark DF. An analytical method for the measurement of cosmogenic 35S in natural waters. Anal Chem. 2015;87(12):6064–6070. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00584

- Hong YL, Kim G. Measurement of cosmogenic 35S activity in rainwater and lake water. Anal Chem. 2005;77(10):3390–3393. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/ac048128c

- Love DL, Sam D. Radiochemical determination of sodium-24 and sulfur-35 in seawater. Anal Chem. 1962;34:336–340.

- Vogl K, Foisnon S, Gesewski P, Winkelmann I. Radiochemical determination of sodium-24 and sulfur-35 in seawater. Bonn (Germany): Federal Research Center for Hydrology; 1985.

- Rossello JA, Maravilla A, Rosato M. The nuclear 35S rDNA world in plant systematics and evolution: a primer of cautions and common misconceptions in cytogenetic studies. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:788911. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.788911

- Hershey A, Chase M. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol. 1952;36(1):39–56. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.36.1.39

- Houghton R, Bennett W. Emergency characterization of unknown materials. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003037668

- Hershey A, Chase M. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in the growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol. 1952;36(1):39–56. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.36.1.39

- Pirieh P, Naeimpoor F. Retrieving sulfur in thiosulfate bio-oxidation: indigenous consortium vs. its dominant isolate Ochrobactrum sp. Bioremediation J. 2023;27(1):1–19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10889868.2021.1990208

- Reed S, Pisaniello D, Behnke G, Burton K, editors. Radiation—ionising and non-ionising: an introduction. London: CRC Press; 2013;544. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003116813

- Garten CT Jr. Fate and distribution of sulfur-35 in yellow poplar and red maple trees. Oecologia. 1988;76(1):43–50. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00379598

- Brown EM, Grace JP, Ranasinghe Arachchige NPR, Bowden NB. Synthesis of sulfur-35-labeled trisulfides and GYY-4137 as donors of radioactive hydrogen sulfide. ACS Omega. 2023;8(30):27576–27584. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c03258

- Rossello JA, Maravilla AJ, Rosato M. The nuclear 35S rDNA world in plant systematics and evolution: a primer of cautions and common misconceptions in cytogenetic studies. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:788911. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.788911

- Wittwer AJ, Stadtman TC. Biosynthesis of 5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenouridine, a naturally occurring nucleoside in Escherichia coli tRNA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;248(2):540–550. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(86)90507-2

- Van den Berghe S, Leenars A, Koonen E, Sannen L. From high to low enriched uranium fuel in research reactors. Adv Sci Technol. 2010;73:78–90. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AST.73.78

- Yuldashev BS, Salikhbaev US. Account and control nuclear materials at the WWR-SM reactor in the Institute of Nuclear Physics, Tashkent. In: Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Safety Related Issues of Spent Nuclear Fuel Storage; 2005 Sep 26–29; Almaty, Kazakhstan;143–145.

- Aden VG, Kartashev EF, Lukichev VA, Lavrenyuk PI, Chernyshov VM, et al. Russian program for reducing fuel enrichment in research reactors. Phys At Nucl. 2005;(5). Series: Physics of radiation damage and radiation materials science; 88:3–9. Available from: https://vant.kipt.kharkov.ua/TABFRAME.html

- Neutron fluency measurements. IAEA Technical Reports Series No. 107. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency; 1970;45–75.

- Lobach YuN, Cross MT. Dismantling design for a reference research reactor of the WWR type. Nucl Eng Des. 2014;266:155–165.

- Ashrapov TB, Karabayev KhKh, Burnashyov OT. Report on the results of resource tests in the WWR-SM TBC type IRT-3M reactor with 36% enriched fuel. Inv. No. 1/491. Tashkent: Institute of Nuclear Physics, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan; 1995.

- Levin VI. Obtaining radioactive isotopes. Moscow: Atomizdat; 1972;132.

- Gledenov YuM, Salatsky VI, Sedyshev PV, Shalan'ski PI. Measurement of the reaction cross section 35Cl(n,p)35S for thermal neutrons. 1996. Available from: https://inis.iaea.org/records/0jybg-6bc08

- Kruchkov EF, Yurova LN. Theory of neutron transport. Moscow: MEPhI; 2007;221.

- Varlachev VA. Neutron transmutation doping of silicon in a pool research nuclear reactor. Abstract of dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Technical Sciences. Tomsk; 2015;29–33.

- Silaev ME, Chertkov YuB. Devices and methods of physical measurements. Tomsk: Publishing House of the Tomsk Polytechnic University; 2008;16–17. Available from: file:///C:/Users/Work/Desktop/pribory_and_metods_fiz_izmer_zac.pdf

- Safin YuA, Karpechko SG. Application of thermoneutron sensors for measuring the flux density of thermal neutrons. At Energ. 1978;46(2):114–115.

- Ashrapov U, Yusupov D, Alieva M, Rustamov N. Monitoring of neutron field of the reactor WWR-SM at reception of phosphorus-33. Univ J Phys Appl. 2019;13(4):63–68. Available from: https://doi.org/10.13189/ujpa.2019.130401

- Oh K, Prelas MA, Rothenberger JB, Lukosi ED, Jeong K, Montenegro DE, et al. Theoretical maximum efficiencies of optimized slab and spherical betavoltaic systems utilizing sulfur-35, strontium-90, and yttrium-90. Nucl Technol. 2012;179:234–242. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.13182/NT12-A14095

- Cherry RN. Ionizing radiation. Introduction. Sources of ionizing radiation. Radiation safety. In: Encyclopedia of Occupational Safety and Health. 4th ed. Geneva: International Labour Office; 1998.

- Das NR, Chattopadhyay P. Chemical consequences of 35Cl(n,p)35S transformation in alkali chloride matrix. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 1984;84(1):185–195.

- Abdel-Rassoul AA, Abdel-Aziz A. Further studies on the production of carrier-free sulphur-35 from pile irradiated potassium chloride targets. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19643300112

- Aly HF, Abdel-Hamid MM. New method for isolation of carrier-free sulfur-35 and phosphorus-32 from neutron-activated potassium chloride. Microchem J. 1972;17(2):215–219. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-265X(72)90177-4

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley